Friday, St. Patrick’s Day in the west, provides the long awaited opportunity to explore the ancient capital of Damascus. Raban Kyrillos is again my guide for the day, and we hitch a ride to Damascus with four seminarians (three a pictured here with one of their teachers) on their way to Beirut (Wa’al No. 1 is the driver). They are going to represent their seminary at a conference of seminarians from around the Middle East. Jimmy (on the left) is a native of Beirut, and his mother is Armenian, he gave me a tour of the seminary on the evening of my arrival (Wednesday) — his English is quite good and we also share a few words in his “mother tongue” of Armenian. I learn later that 4 seminarians from Bikfaya also attend the conference and tell me about meeting the seminarians from Damascus and discovering their mutual acquaintance with “Fr. Walter from Canada.”

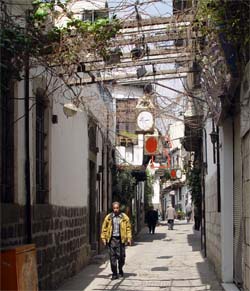

The streets of Damascus are much broader and more open than those of Beirut. There is noticeably less traffic, but this is Friday after all, the day of the Moslem Sabbath — most businesses and services are closed for the day.

The BMWs, Mercedes, Hummers and Jaguars that are common enough in Beirut, seem nearly absent in Damascus. But there are quite a few gems like the DeSoto (c 1950) pictured here — “It’s delightful, it’s De-lovely!” Cars like these are generally a bit worse for wear, but impressive just the same.

It  takes about a half an hour to reach the old city, and we eventually

find ourselves standing on the “street called Straight.” My Lonely Planet

guidebook reports that it isn’t straight at all but bends slightly in a couple

of places, leading Mark Twin to observe, in The Innocents Abroad, that

St. Luke in the Bible is “careful not to commit himself; he does not say is is

the street which is straight, but the street which is called

Straight. It is a fine piece of irony; it is the only facetious remark in

the Bible, I believe.”

takes about a half an hour to reach the old city, and we eventually

find ourselves standing on the “street called Straight.” My Lonely Planet

guidebook reports that it isn’t straight at all but bends slightly in a couple

of places, leading Mark Twin to observe, in The Innocents Abroad, that

St. Luke in the Bible is “careful not to commit himself; he does not say is is

the street which is straight, but the street which is called

Straight. It is a fine piece of irony; it is the only facetious remark in

the Bible, I believe.”

I didn’t see enough to evaluate the straightness of the street, but I can certainly report that it is very narrow. Were Jesus teaching about wealth today, he might say something like, “It is as hard for a rich man to enter heaven as it is for a tourist bus to drive down the street called Straight.” — and of course a big one does drive by, forcing us into the doorway of a shop to avoid the squeeze.

Before reaching the street called Straight, we stop at the old Syrian

Orthodox Patriarchate on Bab Toma Street. There is a memorial liturgy underway, and

the church is about two thirds full of worshippers who have come to mark the 40

day anniversary of the death of a young mother — keeping such an anniversary

common practice for Orthodox Christian families.

liturgy underway, and

the church is about two thirds full of worshippers who have come to mark the 40

day anniversary of the death of a young mother — keeping such an anniversary

common practice for Orthodox Christian families.

Unlike the Armenians, the sanctuary curtain — a common feature among the Oriental Orthodox — is neither black nor closed for the duration of Lent. (Ardavazt Serpazan would like to see an end of this uniquely Armenian practice, at least at the Catholicosate in Antelias.) The curatin is opened at one point and we can see the celebrant. red seems to be the preferred colour of copes among the Syrian Orthodox, regardless of the liturgical season.

The devotion of the faithful is very impressive, old and young alike in the congregation seem very much in communion with the living God, and their traditional faith is very much an anchor for the storms of life and tragedies like the loss of a young mother.

We pause briefly to visit Greek Catholic Cathedral where the Divine Liturgy is taking place. The music is particularly rich and the cathedral is packed with believers. Click here for a short movie.

I am very pleased when we come next to the Armenian Cathedral for the Diocese

of Damascus.  Armenians have lived in

Damascus for at least four centuries, and their current Cathedral was

constructed in the 1860s.

Armenians have lived in

Damascus for at least four centuries, and their current Cathedral was

constructed in the 1860s.

An acolyte, pleased to learn that I speak a bit of Armenian, is kind enough to open the curtain so that we can have a peak at the altar (pictured here).

A funeral has just taken place — it seems a busy day for funerals throughout

the Christian Quarter — and I mention to the Armenian priest who has taken the

service,

that there is a young man, Deacon Aram, at the seminary in Bikfaya who

is a native of Damascus. The priest is overjoyed to hear this for he is none

other than Aram’s father! He insists that we meet the new bishop, The Rt. Revd

Armash Nalbandian, a member of the Brotherhood of the Catholicosate of

Etchmiadzin in Armenia. Bishop Armash is clearly loaded with work, but happy to

make time for a short visit. He has fond memories of meeting Canon Philip

Hobson, another recipient of the Scholarship of St. Basil the Great who spent

three months in Etchmiadzin in 1998. Armash Serpazan has served as prelate for

the diocese for two years, and was finally anointed bishop only a few weeks

before our meeting.

that there is a young man, Deacon Aram, at the seminary in Bikfaya who

is a native of Damascus. The priest is overjoyed to hear this for he is none

other than Aram’s father! He insists that we meet the new bishop, The Rt. Revd

Armash Nalbandian, a member of the Brotherhood of the Catholicosate of

Etchmiadzin in Armenia. Bishop Armash is clearly loaded with work, but happy to

make time for a short visit. He has fond memories of meeting Canon Philip

Hobson, another recipient of the Scholarship of St. Basil the Great who spent

three months in Etchmiadzin in 1998. Armash Serpazan has served as prelate for

the diocese for two years, and was finally anointed bishop only a few weeks

before our meeting.

The laughter of little children greets us as we leave the Bishop’s office. As

usual, wherever one finds an Armenian church,an Armenian school is sure to be

close at hand!

Crossing the street called Straight, we head down a small side street

along the edge of the Christian Quarter. Along the way, Raban Kyrillos meets a

couple of elderly Syrian deacons who congratulate him on his new monastic

hood. We stop and pray at a small shrine dedicated to St. George, before making

our way to one of the most famous Biblical sites of Damascus, and perhaps the

most humble. We descend a couple flights of stairs from street level to reach

the St. Annanya’s Home. Now a small chapel, it is simply decorated with three

lovely carved wooden panels behind the altar that tell the story St. Paul’s

famous visit to the city of Damascus.

Crossing the street called Straight, we head down a small side street

along the edge of the Christian Quarter. Along the way, Raban Kyrillos meets a

couple of elderly Syrian deacons who congratulate him on his new monastic

hood. We stop and pray at a small shrine dedicated to St. George, before making

our way to one of the most famous Biblical sites of Damascus, and perhaps the

most humble. We descend a couple flights of stairs from street level to reach

the St. Annanya’s Home. Now a small chapel, it is simply decorated with three

lovely carved wooden panels behind the altar that tell the story St. Paul’s

famous visit to the city of Damascus.

Reading in the Semitic way from right to left, the story of St. Paul’s conversion is depicted on the three panels. First (right), on the road to Damascus, where he intends to annihilate the Christian population in refuge there, Saul is knocked from his horse, blinded, and hears the voice of the Lord, “Saul, Saul why are you persecuting me!” God speaks to St. Annanya (Ananias) telling him to set aside his fear of the infamous persecutor and to go to Saul who is now in Damascus, repentant and ready for conversion. St. Ananias blesses Saul and scales fall from his eyes restoring his sight. He is then baptised, traditionally at this very spot, taking the new name of “Paul”. Later, to save him from the authorities determined to arrest and punish him, Paul is lowered from the walls of the city in a basket (third panel).

Leaving the Church of St. Annanya, we head west toward the Moselm half of the old city. Along our way we see this group of Christian locals waiting to buy flat bread fresh from the oven — and the aroma of the fresh bread fills the air.

A

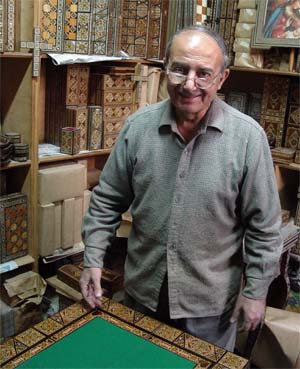

few steps later, we walk by the open door of George Sleiman & Brothers,

wooden mosaic workshop. Mr. Sleiman is a very pleasant fellow who speaks an

elegant English. His three sons are all accomplished singers, one developing a

career as an opera singer in Belgium, another directing the Syrian National

Choir.

A

few steps later, we walk by the open door of George Sleiman & Brothers,

wooden mosaic workshop. Mr. Sleiman is a very pleasant fellow who speaks an

elegant English. His three sons are all accomplished singers, one developing a

career as an opera singer in Belgium, another directing the Syrian National

Choir.

He is pleased to take the time to show us around the workshop and explain his

craft. First a variety of woods are cut into strips in a variety of shapes.

These are bound together and dipped in glue forming, once dried, a solid shape

which is then sliced to provide thin mosaic panels like the one here in Mr.

Sleiman’s hand. His brothers share in this work and they are the last of several

generations of mosaic makers. Soon this small family business will have to

close.

variety of shapes.

These are bound together and dipped in glue forming, once dried, a solid shape

which is then sliced to provide thin mosaic panels like the one here in Mr.

Sleiman’s hand. His brothers share in this work and they are the last of several

generations of mosaic makers. Soon this small family business will have to

close.

Our path takes us on into the Moslem part of the old city and we reach the great wall and closed east gate of the Umayyad Mosque. My Lonely Planet guidebook describes this as “one of the most magnificent buildings of Islam, and certainly the most important religious structure in Syria. … In terms of architectural and decorative splendour it ranks with Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, while in sanctity it is second only to the holy mosques of Mecca and Medina; and it possesses a history unequalled by any of these.” People are seen here entering the courtyard of the Mosque, shoes in hand!

The Lonely Planet continues, “Worship on this site dates back 3000 years to

the 9th century BC, when the Aramaeans built a temple to their god, Hadad

(mentioned in the Book of Kings in the Old Testament). With the coming of the

Romans the temple became associated with the god Jupiter and was massively

expanded. … After Constantine embraced Christianity as the official religion of

the Roman Empire, Jupiter was ousted from his temple in favour of Christ. The former

pagan shrine was replaced by a basilica dedicated to John the Baptist, whose

head is said to be contained in a casket here.” The casket today is housed in

the shrine, pictured here — and Moslem believers come from around the world to

venerate the tomb of the prophet John.

Jupiter was ousted from his temple in favour of Christ. The former

pagan shrine was replaced by a basilica dedicated to John the Baptist, whose

head is said to be contained in a casket here.” The casket today is housed in

the shrine, pictured here — and Moslem believers come from around the world to

venerate the tomb of the prophet John.

When the Muslims entered Damascus in AD 636 they converted the eastern part

of the basilica into a mosque but allowed the Christians to continue their

worshp in the western part. (This picture was taken facing west.)

This arrangement continued for about 70 years. But, during this time, under Umayyad rule Damascus had become capital of the Islamic world and the caliph, Khaled ibn al-Walid, considered it necessary to empower the image of his city with ‘a mosque the equal of which was never designed by anyone before me or anyone after me.’”

The mosque is full of people. Many are simply enjoying the Moslem Sabbath and time with the family — children have a field day sliding on the polished stone surface of the great courtyard and dancing on the carpets inside. Others, like the women pictured here, come in pilgrimage. The Lebanese Shiite party Hezboullah seems to have organised a massive pilgrimage for the weekend … On the we back to Beirut the next day (Saturday), we see perhaps as many as 50 buses full of the Hezboullah faithful, lined up and waiting to cross into Syria to visit the great mosque.

And there are those who rely on the busy flow of visitors, like these street

urchins, enjoying a break from begging with a game of cards. One, with the

beige jersey with brown sleeves, working the crowded entrance to the mosque

comes up to us as we enter and again as we leave, with sorrowful eyes patting

his tummy and pointing to his mouth, and then his hand stretched out for a gift

(and a small coin won’t do!) — a well rehearsed routine no doubt, but hard to

pass by without digging into our pockets for spare change!

begging with a game of cards. One, with the

beige jersey with brown sleeves, working the crowded entrance to the mosque

comes up to us as we enter and again as we leave, with sorrowful eyes patting

his tummy and pointing to his mouth, and then his hand stretched out for a gift

(and a small coin won’t do!) — a well rehearsed routine no doubt, but hard to

pass by without digging into our pockets for spare change!

The famous Damascus souq (covered market) is closed today, but here and there shops, likely owned by Christians, display their wares, adding more than a bit of colour to the Old City of Damascus.