I doubt that many of us tend to think of Syria as a Christian country, and it’s not predominantly so, of course. This said however, Christians do make up about 10% of the population and they are well treated and their communities in reasonably good health — certainly not the kind of steady exodus of Christians away from Syria as seems to be the case in Lebanon.

Sayyidnaya is one of several Christian communities to the north and west of Damascus, and there are a number of monasteries, churches and pilgrimage sites within about 30 km of the Syrian Patriarchate. Three important Christian sites can be seen in this photo (above) taken from the window of my room in the Patriarchate. If you look closely you can spot the Cherubim Greek Orthodox Monastery at the top of the mountain, St. Thomas Church and Roman Catholic Monastery midway down, and to the lower right of St. Thomas and reigning over the village of Sayyidnaya, the convent complex housing the major pilgrimage site of Our Lady of Sayyidnaya (the interior of the convent’s main church is pictured above).

On Thursday, March 16, I join the community for Matins at 7 a.m.; and my

appreciation of the service is increased because of wonderful conversations with

a few of the monks in the course of my first evening at the Patriarchate. One,

le père Josef (the bearded monk on the right facing us in this picture), speaks

wonderful French which he perfected during a 3 year program of Biblical

Studies in Paris. He is as delighted as I am to find someone capable of a full

conversation in that language.

wonderful French which he perfected during a 3 year program of Biblical

Studies in Paris. He is as delighted as I am to find someone capable of a full

conversation in that language.

The sisters and monks are easy to spot in a crowd thanks to the hood that is emblematic of the religious life in the Syrian and Coptic traditions (I’m told the Copts adopted this from the Syrians). The sharp points in a line over the ears represent the Crown of Thorns, and the larger crosses in two groups of 6, on either side of the head, represent the Twelve Apostles.

Breakfast is simple but delicious, despite the Lenten restrictions — no

animal products (meat, dairy and eggs); and it is very much like the breakfasts

served in the Armenian community. I enjoy the flat bread with a thin layer of the

sesame-thyme spices (upper right corner), mixed with some of the rich olive oil

for which Syria is famous. This is garnished with tomato and cucumber. There is

even some halva available for a sweet finish to the meal (which one wraps in

flat bread as well — most everything is eaten in or with flat bread in the

Middle East!) The star attraction of the meal, however are the Patriarchate’s

own very tasty olives, grown in the compound of the patriarchate and put up by

the seminarians and religious themselves. These remind me of the olives my Uncle

Joe harvested and prepared each year in my native California.

enjoy the flat bread with a thin layer of the

sesame-thyme spices (upper right corner), mixed with some of the rich olive oil

for which Syria is famous. This is garnished with tomato and cucumber. There is

even some halva available for a sweet finish to the meal (which one wraps in

flat bread as well — most everything is eaten in or with flat bread in the

Middle East!) The star attraction of the meal, however are the Patriarchate’s

own very tasty olives, grown in the compound of the patriarchate and put up by

the seminarians and religious themselves. These remind me of the olives my Uncle

Joe harvested and prepared each year in my native California.

I eat breakfast in the company of one of the newest members of the community,

Rabban Kyrillos (pictured here, right) who graduated from seminary just the week

before my arrival and was cloaked in the hood of the Syrian cenobite during

Sunday’s celebration of the

Feast of St. Ephraim, patron of the seminary and of the

Syrian monastic community. Rabban Kyrillos (formerly Carlos) is taking

medication, so he is allowed to join me while his monastic brothers and sisters

observe the Lenten fast which for them means no food until noon in addition to

the usual orthodox Lenten diet.

Feast of St. Ephraim, patron of the seminary and of the

Syrian monastic community. Rabban Kyrillos (formerly Carlos) is taking

medication, so he is allowed to join me while his monastic brothers and sisters

observe the Lenten fast which for them means no food until noon in addition to

the usual orthodox Lenten diet.

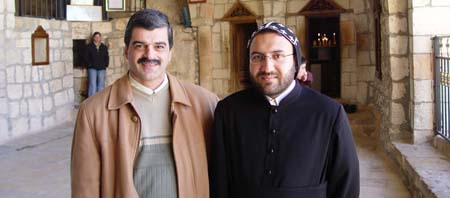

Father Matta keeps us company while we eat. He is an assistant director of the seminary, I believe, and is happy to practice his English. He has been working hard to improve his English language skills in preparation for a program in Peace Making this summer at the Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia. Sr. Tabitha has arranged with Fr Matta to have Rabban Kyrillos serve as my guide for the day, and a rather full programme with eight nearby monasteries, churches and pilgrimage sites lined up for visits. Fr. Matta has hired the services of a min-van for the day, another Wa’al is our driver, and Dr. Sa’ad Hazim (pictured left), also visiting the Patriarchate joins us for the day.

Dr. Sa’ad is an orthopedic surgeon from Mosul, Iraq. He is travelling through

the region in a desperate search for a way out of Iraq for his family. For

security reasons, he has had to close his clinic in Mosul, and reports that life

as a Christian in Iraq has become quite dangerous. Anti-American sentiment often

boils over in attacks on the small Christian population in the country.

He gives a

chilling account of what he has seen during his rounds at the emergency ward of

his local hospital. His desperation is growing as he discovers that the other

countries in the region are steadily closing their doors to Iraqi immigration.

Syria has rejected his application to move here, and he fears that Jordon will

do the same. He has a brother in Detroit and would be very willing to move his

family to North America, but here again the road blocks are enormous despite the

reputed shortage of orthopedic surgeons in North America. If anyone reading this

has any possibility of assisting Dr. Sa’ad in his search for a safe haven for

his family (he has three young sons) or wishes to send a word of encouragement,

he can be reached at saadhazim64@yahoo.com

He gives a

chilling account of what he has seen during his rounds at the emergency ward of

his local hospital. His desperation is growing as he discovers that the other

countries in the region are steadily closing their doors to Iraqi immigration.

Syria has rejected his application to move here, and he fears that Jordon will

do the same. He has a brother in Detroit and would be very willing to move his

family to North America, but here again the road blocks are enormous despite the

reputed shortage of orthopedic surgeons in North America. If anyone reading this

has any possibility of assisting Dr. Sa’ad in his search for a safe haven for

his family (he has three young sons) or wishes to send a word of encouragement,

he can be reached at saadhazim64@yahoo.com

The first stop on our pilgrimage to the some of the sacred sites for Syrian

Christianity begins with a stop at a rocky outcropping high above the Syrian

plane said to be

the place where the prophet Elijah hid from the forces of Queen

Jezebel, sent to find and kill him. We enter an ancient church in front of the

grotto. (Raban Kyrillos looks out from the grotto itself to the great plain

below, in the picture, above.) The obvious antiquity of carvings and the

remaining frescoes portraying episodes in the life of the great prophet suggest

that this has been a site of some importance for centuries. I’m not too sure who

the two figures here are intended to represent. Elijah and his successor Elisha?

Some of the bright coloring that would have originally covered the carvings can

still be seen.

the place where the prophet Elijah hid from the forces of Queen

Jezebel, sent to find and kill him. We enter an ancient church in front of the

grotto. (Raban Kyrillos looks out from the grotto itself to the great plain

below, in the picture, above.) The obvious antiquity of carvings and the

remaining frescoes portraying episodes in the life of the great prophet suggest

that this has been a site of some importance for centuries. I’m not too sure who

the two figures here are intended to represent. Elijah and his successor Elisha?

Some of the bright coloring that would have originally covered the carvings can

still be seen.

The father of these two treasures

welcomes us to the Elijah shrine and guides us

down the nearly 200 steps to the grotto. He and his family live in a small house

near the car park, and a Christian school is being built opposite. It is clear

that the situation for Christians in Syria is much better than for those in Dr.

Sa’ad’s troubled homeland of Iraq.

welcomes us to the Elijah shrine and guides us

down the nearly 200 steps to the grotto. He and his family live in a small house

near the car park, and a Christian school is being built opposite. It is clear

that the situation for Christians in Syria is much better than for those in Dr.

Sa’ad’s troubled homeland of Iraq.

It is not surprising to find public structures like this archway (below) in Syria; and I see several of these during my short visit. The western press and politicians have done a good job preparing me to see public signs of the country’s “hereditary dictatorship.”

What is surprising is to find portraits, particularly of al-Assad senior, prominently displayed in the receiving rooms of the monasteries we visit. Syrian Christians give much of the credit for the stability and security they enjoy to departed President Hafez al-Assad (above, right) and to his son the new President Bashar al-Assad. The senior al-Assad had a great appreciation for the Christian population, and his son seems to be preserving this heritage. Religious intolerance is frowned upon and can lead to heavy fines or even imprisonment.

We next stop to explore the Aramaic village of Ma’aloula. The houses here are

built on the slopes of a rocky cliff that encloses the village; the houses are

constructed of stones with flat beam roofs. Most of the inhabitants are

Greek-Catholic and have preserved in their spoken language a dialect of Syriac

(Aramean). We visit the Monastery of Mar Sarkis (St. Sergius) with its Byzantine

church and Byzantine-period tombs cut into the rock behind. From there

we walk along

a deep gorge cut into solid rock, to the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Tekla

in the village below where one of the sisters operates the crowded giftshop

pictured here.

we walk along

a deep gorge cut into solid rock, to the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Tekla

in the village below where one of the sisters operates the crowded giftshop

pictured here.

“Saint Tekla was the first Christian woman to be exposed to torture and persecution for the sake of her faith in Jesus Christ. She was given the title of ‘equal to the apostles’ because her mission was similar to theirs, and many came to the Christian faith thanks to her efforts. This is why she is called: “Mar Tekla” — the word ‘Mar’ is the masculine form of the word ’saint’ and she was awarded this name due to her shared mission with the apostles.” — from http://www.maaloula.net/src/tbrikhta.htm

After a wonderful lunch of mezze and fried fish (allowed in Lent) at the

Ma’aloula Hotel overlooking the village and the rocky gorge below, we turn back

towards the Patriarchate to visit the monasteries of Sayyidnaya.

of Sayyidnaya.

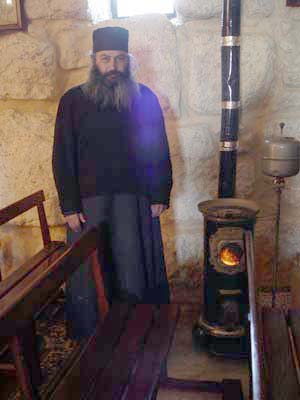

After a very long climb up to the summit of Mount Qalaun overlooking the village, we reach the Greek Orthodox monastery of the Cherubin; and at 2000 meters, it can certainly be said that the monastery is rather close to the angels! It’s aged stone chapel testifies to it’s pre-Christian antiquity. Once a pagan temple, the site is now home to a monastery of friendly and welcoming Orthodox monks, like the one pictured here keeping watch in the monastery chapel.

Our driver, Wa’al is particularly pleased to arrive at the monastery because

this provides the opportunity to visit with a good friend

and former co-worker at

the Sheraton Hotel in Ma’arat Sayyidnaya, not far from the new Syrian

patriarchate. This young man has left the world and joined the monks, and seems

to be doing very well by it all, as his smile and warmth betray. We are invited

in for bitter coffee (flavoured with cardemon), and sweets; and we are not

allowed to leave empty handed either. We each receive gifts of monastery-made

apple vinegar and jam.

and former co-worker at

the Sheraton Hotel in Ma’arat Sayyidnaya, not far from the new Syrian

patriarchate. This young man has left the world and joined the monks, and seems

to be doing very well by it all, as his smile and warmth betray. We are invited

in for bitter coffee (flavoured with cardemon), and sweets; and we are not

allowed to leave empty handed either. We each receive gifts of monastery-made

apple vinegar and jam.

Halfway down the hill we stop at the Church of St. Thomas, said to have been founded by the Apostle on his way to India — the Syrian Orthodox are particularly numerous in India (more than a million) and are known as the Mar Thomas Christians, living in the province of Kerula for hundreds of years. There are many cave hermitages and other former monastic dwellings in the region. It is said that in the hey-day of desert monasticism (2nd-4th centuries), there were thousands of monks living in the Syrian desert.

Soon we arrive at the most important pilgrimage site and monastic

foundation in the region, the convent shrine of Our Lady of Sayyidnaya. Legend

has it that Byzantine emperor Justinian founded the convent in the 6th century.

The emperor was reputedly on a hunting expedition when he spotted a fine white

deer, when he drew his bow and prepared to take the animal, the deer was

miraculously transformed into Our Lady who asked Justinian to build a church in

her honour on the site. The main attraction in the small pilgrimage shrine

(pictured below) is a portrait of Our Lady said to have been painted by St. Luke

himself.

site and monastic

foundation in the region, the convent shrine of Our Lady of Sayyidnaya. Legend

has it that Byzantine emperor Justinian founded the convent in the 6th century.

The emperor was reputedly on a hunting expedition when he spotted a fine white

deer, when he drew his bow and prepared to take the animal, the deer was

miraculously transformed into Our Lady who asked Justinian to build a church in

her honour on the site. The main attraction in the small pilgrimage shrine

(pictured below) is a portrait of Our Lady said to have been painted by St. Luke

himself.

The convent of Our Lady in Sayyidnay and the Mar Tekla’s shrine in Ma’aloula are hugely popular to this day, and apparently as important to the Moslem population as to the Christians of Syria. The main church of the convent is closed, but Dr. Sa’ad is clever enough to whisper a few words to one of the sisters, explaining that “abouna” (Arab for “father”) from Canada would like to pray in the church. Before long the doors are open, and we take time to visit the chapel pictured at the beginning of this post. Word also reaches Mother Kristina, who was consecrated the new Mother Superior only a couple of weeks ago (February 26).

Once again an we are invited to stop for a short visit, and we join Mother

with a couple of other visitors (notably a silver smith who has just repared an

intricate processional cross) for another round of bitter coffee and sweets.

Again we receive gifts: a key chain,

holy cards, small bags of incense — Middle Eastern

hospitality is very much the rule rather than the exception, and we have

received small gifts at every stop along the way today.

holy cards, small bags of incense — Middle Eastern

hospitality is very much the rule rather than the exception, and we have

received small gifts at every stop along the way today.

Mother kindly agrees to have her photo taken. She tells me that there are 90 sisters in the community, and that they operate a home for disabled children and a school in addition the busy pilgrimage shrine with its thousands of visitors.

After a short visit to the Syrian Orthodox Church in the village, we head back to the Patriarchate, stopping along the way at what Dr. Sa’ad calls the “local supermarket” for a long distance phone card.

Once back at the Patriarchate, I make my way to my room for a rest. It’s been

a very full day indeed. We left the Patriarchate around 9:30 a.m. and it is

nearly 5 p.m. when we return. I am just about to slip off for a short snooze

when there is a knock at my door and one of the monks asks if I would like to

meet his Holiness the Patriarch. I answer in the affirmative, of course, and

follow the monk up the stairs to the Patriarch’s offices, beside the seminary

chapel. Dr. Sa’ad is there as well, and his Holiness takes great pains to listen

to his sad story. While the conversation is entirely in Arabic, I can see that

his Holiness is very concerned about the plight of the Syrian Orthodox in Iraq,

and particularly in Mosul, and wants to help. The Patriarch is himself a native

of Mosul, and was bishop there for a couple of years. Sr. Tabitha feels the same

way. A native of Baghdad, she has asked his Holiness to transfer her to the

convent there — I tell her that this news will not set well with her friends,

the Sisters of St. John the Divine, in Toronto. After awhile, the Patriarch

shifts his attention to me and asks, “And how is my good friend Bishop Henry

Hill doing?” I explain Bishop Henry’s struggle with the caprices of old age, and

his Holiness gives me a bronze cross commemorating the Patriarch’s silver

jubilee to take to Bishop Henry, along with his Holiness’s warmest regards.

Patriarch Zakka asks if I am being treated well, and whether I have everything I

need. He is concerned that my visit is far too short, and invites me back again

to stay for as long as I’d like.

about the plight of the Syrian Orthodox in Iraq,

and particularly in Mosul, and wants to help. The Patriarch is himself a native

of Mosul, and was bishop there for a couple of years. Sr. Tabitha feels the same

way. A native of Baghdad, she has asked his Holiness to transfer her to the

convent there — I tell her that this news will not set well with her friends,

the Sisters of St. John the Divine, in Toronto. After awhile, the Patriarch

shifts his attention to me and asks, “And how is my good friend Bishop Henry

Hill doing?” I explain Bishop Henry’s struggle with the caprices of old age, and

his Holiness gives me a bronze cross commemorating the Patriarch’s silver

jubilee to take to Bishop Henry, along with his Holiness’s warmest regards.

Patriarch Zakka asks if I am being treated well, and whether I have everything I

need. He is concerned that my visit is far too short, and invites me back again

to stay for as long as I’d like.

The hospitality I have been shown in the Middle East, from Catholicos Aram and Patriarch Zakka and from all of the people who welcomed us today, is simply amazing. We in the west let busy-ness get in the way of this most basic of human graces; and we have much to learn about real priorities from the people of the Middle East.